|

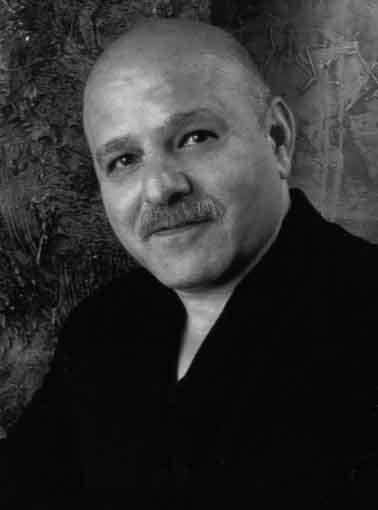

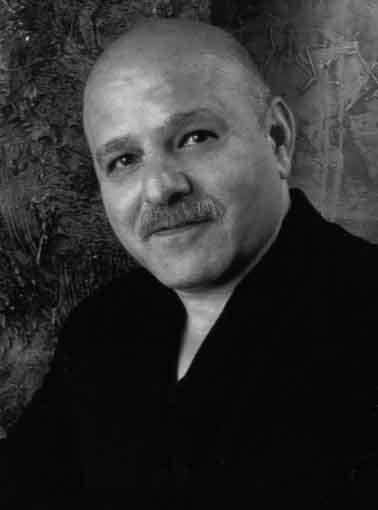

Noah Creshevsky began musical study at

the Eastman School of Music. He

graduated from the State University of

New York at Buffalo, where he was a

pupil of VirgilThomson, arid studied with

Nadia Boulanger in Paris and

Fontainebleau. His master’s degree is

from the JulWard School, where he was a

pupil of Luciano Berio.

Creshevsky’s work has been supported by

grants and awards from the National

Endowment for the Arts, the New York

State Council on the Arts, and ASCAP.

It has been published by Alexander

Broude, released on recordings, and

performed and broadcast in the United

States, Europe and Asia.

A professor of music at Brooklyn College

of the City University of New York,

Creshevsky has served on the faculties of

the Juilliard School and Hunter College

and as a visiting professor at Princeton

University.

Creshevsky has been composing electronic

music for more than twenty years. Many

of his works explore the boundaries of real

and imaginary ensembles though the

fusion of opposites: music and noise,

comprehensible and incomprehensible

vocal sources, human and superhuman

instrumental skIlls.

His latest music integrates electronic and

acoustic sources to create superperformers

— hypothetical virtuosos who transcend

the limitations of individual performance

capabilities.

The result is electronic music of

symphonic proportion in which expansive

gesture and a vast sonic palette are

combined to form expressive ties between

the real and unreal, man and superman.

|

|

|

|

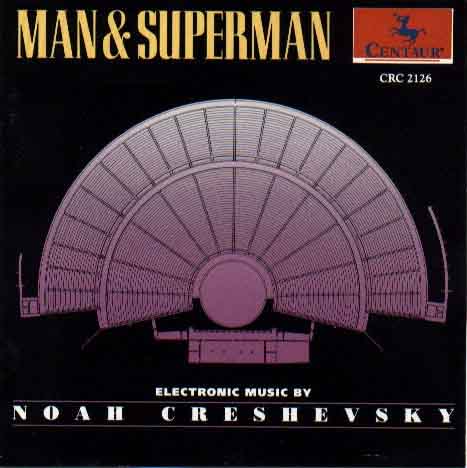

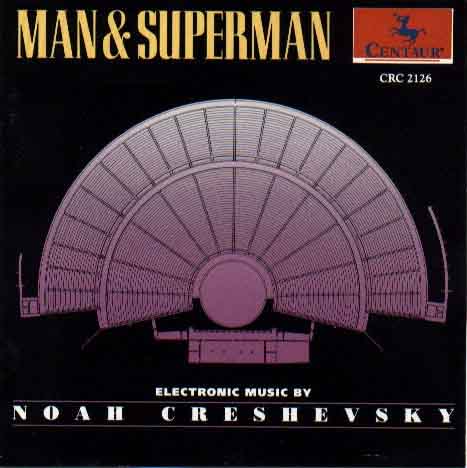

| Variations (1987) | 16:35 |

| Variations

1987

“It is in looking for possibilities that

you find reality. . . . This year I

received a letter which went thus:

‘Mademoiselle, the cow is better, my

wife is dead, the trees are shooting up.

My respects.’ Well, that’s a very real

letter.” — Nadia Boulanger

The digital sampler and the computer

have made possible an unprecedented

degree of technical accuracy and

efficiency, and have made available

the sounds of all things and the music

of all times.

flexibility.

I chose in Variations to spend time

with the ancient and parsimonious

notion of economy by restricting my

choices to pitched sounds only. Even

so, a great many timbres are

introduced and united.

The principle of perpetual variation

operates throughout; sectional

repetitions are interrelated solely

through a few prominent motivic and

rhythmic elements.

Yeta kind of puritanical restraint and

frugality persist. I am skeptical of the

view that economy should be

considered the proper mission of all

human endeavor, and celebrate

abundance — both in the expanded

palette of musical sounds and

technologies, and in the existence of

more and better choices and enhanced |

| |

| Electric String Quartet (1988) | 6:05 |

| Electronic String Quartet

1988

“We bake a cake and it turns out tha

the sugar was not sugar but salt. I n

sooner start to work than th

telephone rings.”

— John Cage, “Juilliard Lecture”

One plays the way one can

One plays the way one can’t

One talks,

One does other things. |

| |

| Memento Mori (1989) | 11:10 |

| Memento Mon

1989

“The boundaries which divide Lif

from Death are at best shadowy an

vague. Who shall say where the on

ends, and where the other begins?”

— Edgar Allan Poe, “The Prematur

Burial”

The fusion in Memento Mon o

radically contrasting material

represents the ever-present awarenes of the human condition, a recognition of our collective identity, and the inevitableility of our common destinations - made every day more movingly evident.

|

| |

| Electric Partita (1990) | 7:54 |

| Electric Partita

1990

“A performance so complete, so wholly

integrated, so prepared, is rarely to be

encountered. Most artists, by the time

they have worked out that much

detail, are heartily sick of any piece

and either walk through it half asleep

or ham it up.”

— Virgil Thomson,

reviewing Wanda Landowska’s

performance of Bach’s Goldberg

Variations, February 22, 1942.

Electric Partita was composed for an

ensemble of improbably accomplished

performers, capable neither of fatigue

nor histrionics, that exists and can

only exist on tape.

Digital dexterity reaches unlikely

levels through the union of the human

hand and the digital computer.

A technical feature of the 14th-

I century isorhythmic motet is the

application of a reiterated pattern of

time values to present a liturgical

cantus firmus.

Of particular appeal are motets in

which the number of notes in the

melody — color — and rhythmic

pattern — talea — do not coincide.

This produces a complex internal order

which is anything but obvious to the

ear.

A concealed interior structure existing

in the realm of abstraction and

I contemplation rather than as

something capable of being detected

by hearing would have pleased the

medieval musician. |

| |

| Talea (1991) | 8:15 |

Talea

1991

A technical feature of the 14th-

century isorhythmic motet is the

application of a reiterated pattern of

time values to present a liturgical

cantus firmus.

Of particular appeal are motets in

which the number of notes in the

melody — color — and rhythmic

pattern — talea — do not coincide.

This produces a complex internal order

which is anything but obvious to the

ear.

A concealed interior structure existing

in the realm of abstraction and

contemplation rather than as

something capable of being detected

by hearing would have pleased the

medieval musician. |

| |

|

|